Reflection:

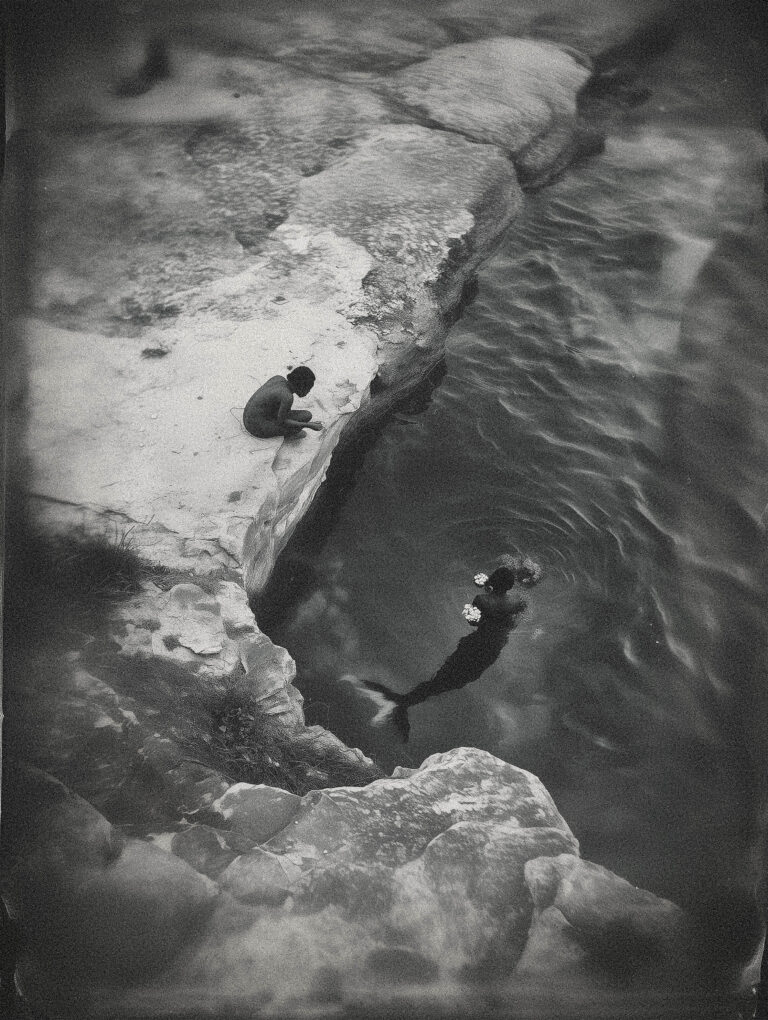

In the Greco-Roman worldview, the young hunter Narcissus stares at his own image in continuous repetition, to the point of losing his life to a kind of self-love. The myth is commonly associated with the colonial power paradigm, in which nothing beyond the self is seen or loved, and through which the dissimilar is nullified. Unlike the Afro-Brazilian water deities, the Iyabás—Iemanjá and Oxum—entities from the Yoruba cosmogony, carry abebés1, reflective war instruments expressing truth and self-knowledge. Reflected images, in addition to empowering them individually and collectively, show what is behind the one who looks. As a simultaneous extension of the front-facing view, this double reflection allows observation in both directions, as well as across times—past, present, and future. Water, the element that carries both Narcissus’ and Oxum and Iemanjá’s narratives, overflows beyond individual reflection by also representing cosmoperceptions that shape collective identities.

Capture:

From a geopolitical perspective, water is movement—it drives migrations, delineates ecosystems, and triggers territorial disputes. Biologically, it is a vital substance for human, animal, and plant life. Symbolically, it reflects autognosis: what traverses, constitutes, and contaminates the self. Like water, photographic language shares a social and political effect as a cultural record reflecting ongoing discussions.

Reel:

Rewinding back to 1888 and Kodak’s slogan: “You press the button, we do the rest”2. From mechanical automation to digital cameras, from excessive consumption on social media to resulting critiques, photography destabilizes and reemerges in new forms, repositioning itself as a post-photographic field. Transcending technical mastery, it expands the grasp of time, ritual, and event. Yet it remains the human’s role to bring gesture, intention, meaning, and memory.

Archive:

“Once upon many times (…). Once upon another story, then another, and another. All a little different. All more or less the same.” 3 So writes São Paulo author Amanda Julieta as she multiplies the experiences of three generations of her family—all Black Brazilian women: between silences, gaps, and fragmented narratives, a curved history is inscribed. Aline Motta, an artist from Niterói, in Water is a Time Machine4, turns lineage, language, and archival traces into acts of denouncement. They all produce counter-archives: strategies of reclamation. They all become their mothers’ ancestors by choosing to reenact their mothers’ existence alongside their own as daughters, just as the spiral time concept theorized by Leda Maria Martins5.

“If the first digital revolution discredited a certain regime of truth, the second now questions memory.” 6 Through dissolution and recomposition with critical fabulation, these artists use the scopic regime to fulfill traditional photography’s role: safeguarding identity and memory. Negotiating with time, however, reconfigures systemic violence: mechanisms that historically reinforced discrimination are also used as tools for its reparation.

Intention:

Mayara Ferrão delves into the failures of representation. Faced with threats to imagination and authorship—concepts often deemed obsolete in post-photography—she uses artificial intelligence as an abebé, a warlike tool bridging the future to a supposedly inaccessible past. Through a strategic game of cooperation involving the research of public domain colonial and post-colonial documents, institutional archives, and impressions from antique stores, she employs poetic writing to generate prompts, which are then subjected to varied treatments: collages, overlays, color and texture applications.

Ferrão adapts the residual to the synthetic, generating visualities absent from archives: Black women full of self, of affection, of the sacred. From imagined but uncaptured photographs of the 19th century, Mayara Ferrão becomes a witness. Unable to return to those experiences, she produces simulated negatives—false in form, true in intent—that counter erasure by fabulating the archive, performing historiographies as social support.

Command:

DSLR EOS Rebel T7i camera, 28 7 wide-angle lens, architectural photography, wide framing. Point of view at 1.50 meters, human gaze. Hyper-realistic image of Galeria Verve. East glass facade, mezzanine 06, Edifício Louvre, São Paulo, designed by Artacho Jurado. Minimalist interior, nearly central column slightly to the left. Three walls: two straight, one curved. Polished concrete floor reflects soft light. White ceiling. Mixed lighting: morning natural light, diffuse white tubular lights, warm directional spotlights. High ceilings give a sense of spaciousness. Six black-and-white photographs, with wide matting margins, aluminum-colored frames. Precisely spaced, they create a contemplative atmosphere.

Treatment:

In the exhibition The First Trace Was Water, Mayara Ferrão activates visualities that converse with the mysteries of Yoruba cosmogony, building a bridge between earth and Orum through imagery. Her works preserve an intimate relationship with the spiritual without reducing it to explanation or spectacle. The apparitions—animals, elements, deities, and mythological figures—challenge the scope of artificial intelligence, which is grounded in colonial paradigms and normative algorithms. Instead of reproducing stereotypical gazes, Mayara subverts their codes: she inserts Black, feminine, lesbian bodies surrounded by axé. Her images become less about representation and more about resistance—between capture and return. One might say: if the machine generates images, we are the ones who truly generate them; if the machine erases images, we are the ones who remember them.

The use of the carte de visite format, reminiscent of the 19th century, reinforces the strategy of reclamation: not exporting alterities for external gazes, but rather returning them to Brazil as a legitimization of Afro-diasporic presence, represented without distortion by the Eurocentric mirror. Through manipulation of AI, critical fabulation, and machine learning techniques, Ferrão returns dissidence to the machine, crafting a counter-pedagogy of images in the face of colonial epistemicide.

Layers:

Perhaps what allows us to associate water with these layers of return and overlay—as a spiral reflection—is its continuous movement cycle through atmosphere, oceans, and continents. The logic of displacement and reappearance: a fragment left behind today will inevitably be carried by the currents—evaporation, flow, infiltration—and found again, transformed, in another time and place. It is this very logic that guides the research of Mayara Ferrão, as well as Amanda and Aline: starting from writing to pass through the image, which, more than a device of capture, becomes a surface of return and deep negotiation.

Notes

1 SANTOS, Mauricio; SILVA, Anaxsuell Fernando da. “90 iyás and abebés: Afro-diasporic matriarchal existences, resistances, and struggles.” In: Revista Calundu, vol. 4, n. 2, Jul–Dec 2020.

2 Available at: www.kodak.com/en/company/page/george-eastman-history/. Accessed Mar 31, 2025.

3 JULIETA, Amanda. In Estela’s Wake. Salvador: ParaLeLo13S Publishing, 2025.

4 MOTTA, Aline. Water is a Time Machine. São Paulo: Fósforo Publishing, 2022.

5 MARTINS, Leda Maria. Spiral Time Performances: Poetics of the Screen Body. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó Publishing, 2021.

6 FONTCUBERTA, Joan. Post-Photography Explained… Porto Alegre: PPGAV/UFRGS, v. 21, n. 35, May 2016.