Academy of Anti-heroes [Academia de Anti-heróis]

Like the work of João GG, the exhibition Academia de anti-heroes is marked by citationism, an accumulation of repertoires and terms that, too, carry many layers of meanings.

Academia, for example, takes us back to Plato’s Academy, located beyond the walls of Athens, founded around 380 BC. and focused on philosophy and the celebration of gods, goddesses and heroes. Another idea that comes to mind is academicism, which established, from the 16th century, in Florence, a series of norms for the teaching of painting that soon spread throughout Europe and later throughout the western world (here including Brazil), and that lasted until they were confronted with what became conventionally modernism in the visual arts.

However, the meaning here refers to something like a military academy, which implies a complete training, both for the body and for the soul, through which the cadets constitute a single, morally elevated and integral body, cultivating the defense of the homeland, even at the cost of their own lives. An example of this type of institution is the Escola de Sagres, which made it possible for the seas, populated with monsters, to bend to the Portuguese and they would discover Brazil in their search for a route to the Indies. In a military academy, cadets quickly learn the importance of working for the collective, nurturing values that are nobler than their individual doctrines.

Poor cadets.

Poor stories of heroism.

This little story is questionable, quite questionable by the way, just as heroism is relative. But what today seems to us like a colonial fairy tale, despite having harmful effects, serves to convey the idea of an epic narrative guided by the heroism of a small nation that was intended to be great.

And here we arrive at another term steeped in history: the hero and, with him, the problematic hero or, simply, the anti-hero.

We tend to trace the idea of the hero back to Greek myths and their Latin versions. Heroes were noble, lofty figures, daughters of gods and humans who served as models for society. In tragedies, even when they err, taken by pride or disproportion (which the Greeks called hubris), heroes are still exemplary, because if their virtues serve as an example to be followed, their mistakes are made so that no one else repeat them.

Heroes were beautiful, virtuous; they represented the values of an era and, as a rule, act from issues that go beyond personal motivations. Matters of the everyday order are only secondary and sometimes not even mentioned about the life of a hero. The epic poem or epic tells the great deeds of these great men, governed by a strict moral ruler, almost superhuman, for the benefit of the community.

Over the centuries, the notion of the hero has changed. Let’s jump to the romantic hero, from the time when kings and nobles lost their strength, and the bourgeoisie spread their values. Instead of the collective, individual autonomy and freedom are the watchwords. This new hero has no choice but to stand against the world. The gods are no longer willing to help him or blow saving dreams into his ears, and he has only himself and his existential emptiness. Sometimes we see their weaknesses and vices – banal, everyday issues.

Don Quixote is the best example of this transition. The ingenious nobleman, a voracious reader of chivalry novels, lived as in the heroic times of yore, guided by his involuntary nonconformity with the world. His convictions, coming from a time of kings that no longer exist, make him see reality in his own way, and his faithful squire is there to make it clear that all he sees are giants in mills.

Brazil is fertile ground for anti-heroes, who are naturally contesting and often marginalized. We know passages such as “the hero without any character” – Mário de Andrade about “Macunaíma” –, or “Be marginal, be hero”, a phrase printed by Hélio Oiticica about the targeted bandit Cara de Cavalo. Perhaps we can include in this spectrum Macabeia, a passive anti-heroine of Clarisse Lispector who wanted to be Marilyn Monroe and lived an emptiness inside her that was only remedied by the thud of the star of an imported car. And if some die at the hands of the police, “My heroes died of overdoses,” Cazuza would say.

Heroes and anti-heroes populate our imagination through Hollywood cinema and Disney animations. In the comic book “Watchmen” by Alan Moore, we follow the time when superheroes were well-liked for regulating a city threatened by crime. When the action of superheroes is prohibited (it is now up to the police to establish order), the superheroes are thrown to the sidelines. Thus, an outlaw anti-hero is born, who continues to hunt criminals for personal satisfaction: his values no longer belong to the collective, as they satisfy an individual opportunity.

Another infamous anti-hero is the extravagant Bandido da Luz Vermelha, who created four personas of bandits, each with a style: one of them had the habit of robbing mansions in São Paulo with his flashlight bought at Mappin.

Problematic heroes fascinate us because their all-too-human whims and weaknesses sometimes sound like virtues, even if questionable, creating identification in us. Eventually, I’ll find you on this front, giving that way in the arduous battle against expired boletos.

Anti-hero, welcome. We appreciate your enlistment in our ranks, but a caveat: what you’ll least find in your training are scenes of humans exercising their anti-heroism. You will be confronted with fragments, traces of narratives that can be stitched at your whim, and you will be responsible for your choices. So it was with Arachne, who made her tapestries so beautiful and provocative to provoke Athena’s wrath. In Passamanaria Ravel, the proto-industrial technique of trimming, in decline since the 18th century, is diverted from its decorative use to allude to this myth narrated by Ovid in “The Metamorphoses”. Arachne, the virtuous weaver transformed into a spider, appears in João GG’s work with the veins of her wooden hands pouring into fabric.

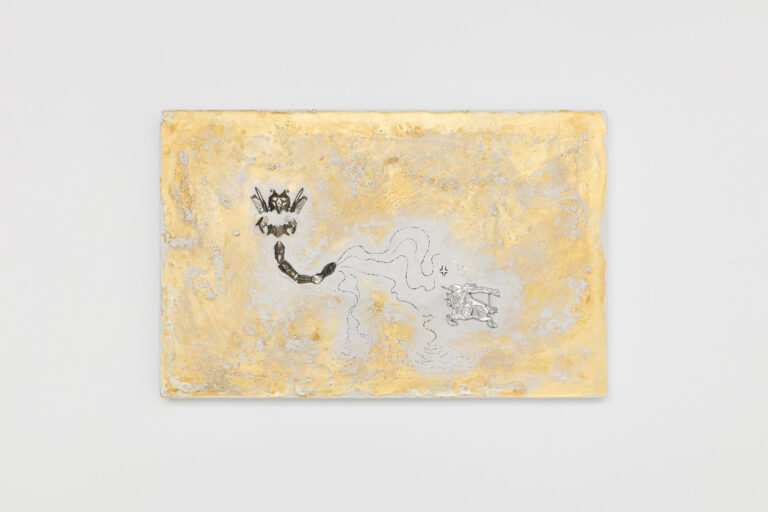

GG presents us with a puzzle of particular mythologies in works in different formats that show deities, entities that emerge amidst rare stones, knickknacks from his personal narrative and objects without pedigree, all mixed together, provoking our sense of value. The human arrogance, which builds to the point of scratching the skies in Rear Window, can at the same time be a Babel condominium meeting with an enraged landlord. And those flames? Would they be an explosive attack or are they fireworks on New Year’s Eve in Copacabana? The cracked window looks more like a trompe l’oeil, so the question remains.

The artist’s choice of plaster blocks and the fresco takes us back to the repertoire, colors and dynamic diagonals of a Giotto, while at the same time we see contemporary and sensational mythologies that dialogue with video clips by Lana del Rey (D’Atena for Giotto). Haute cuisine served by the kilo buffet. In Entourage we are not offered dinner, but their leftovers may come from a fourteen-hundred-year-old family that still proudly flaunts their silverware.

And then there appears in Curupira Galego a redheaded, sneaky and specular imminence: his goatee is orange – a possible miscegenation between indigenous and barbarian colonizers – or is this red streak just a metaphor for his pyromania that protects the forests? The legend of this trickster from the tropics goes the opposite way of colonization: the curupira, initially roaming the Amazon, descends through Araguaia towards the Center-West. But perhaps our Galician anti-hero does not always succeed and so we glimpse, as in It is hot in Fiztcarraldo, a barren Pantanal or Amazon where, decades before, Fitzcarraldo cleared dense forest to drive his absurd ship to the heart of the jungle in search of the rubber.

Another aspect of these frescoes is that they contain more than one plane of representation. Its apparent simplicity, as if we were seeing a fragment of a flat scene where what is below is the seabed and what is above is the sky, is sometimes incomprehensible if we do not think that the same composition is, simultaneously, also the view from a drone commanded by a helicopter, piloted by paparazzi or a bored Zeus. In a Naval Battle, this type of representation superimposes, on the same plane, the board with my ships and the board on which I risk where your ships, opponents are, so that nothing contains only what we apprehend in a first glance.

Each block is an amalgamation of elements, a repository of layers of different materials in which narrative suggestions accumulate without canceling each other out. We often have parodies – in the sense of a dialogue with another work – but Apollonian parodies, sometimes self-ironic. And yet, they result in icons.

The following information may not help at first, but Disney almost went bankrupt for having devoted so many resources to “Fantasia”, until today its masterpiece. This kamizake bet on art is represented in Worshiper of the King and is of the same degree of sacrifice that the bronze knights of “The Knights of the Zodiac” made by offering their own blood so that their armor would regenerate after battles.

There is also a reference, in a wild career, to the obsolescence and evolution of the means of representation at the same time; not so much to the programmed obsolescence of our smartphones, but to the human being himself, obstinate in creating a highly technological environment, hostile to himself. All these pieces of plaster could be hanging in the vast halls of a haunted castle, in a Chateau Terrible that populates our repertoire of children obsessed with drawings, video games and anime. But it is not given to us to know, only to speculate what may be inside this hermetic, timeless and fallen castle, built on unattainable ideals.

It is in this fragmentary and ominous universe that we invite you to project your anxieties, anxieties and expectations, to finally be awarded the deserved title of anti-hero.

John acts a bit like Sid, the evil neighbor next door from Toy Story, who plays at destroying and reassembling toys, disfiguring them to form a new figure; procedure not unlike that which the Greeks did when lending human parts to bull bodies. This was all a long time ago, but it was also yesterday. Maybe the boy wasn’t that cruel, but history told us he was and we, naive drunks on fantastic, believe. Once upon a time there was an artist named João GG who thought of creating a mix of a horror tunnel and a room of mirrors for adults, and you are now part of it.

![Foguinho [Little fire]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/sitejoaogg4-768x759.png)