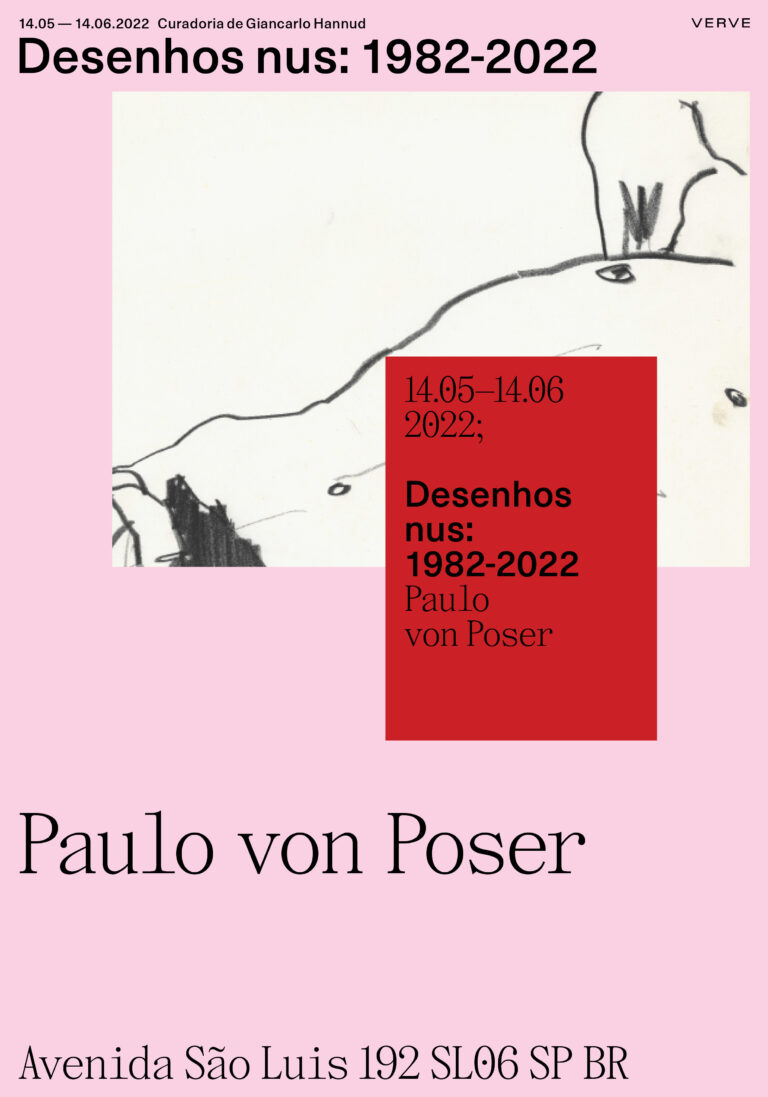

Naked Drawings: 1982-2022 [Desenhos nus: 1982-2022]

“We were raised to look out for each other, weren’t we?” – Edgar Degas

In the beginning was the look. The look became the body, and the body was the drawing. This act speaks to us, through a return to the beginning, again from the look. In this sense, the epigraph that opens this text seems to be a good place, as apt as any other, from which to start an approach to the work of Paulo von Poser, as it brings us closer to one of the possible understandings of an artist whose primary sensitivity seems to be that of the complex, but elusive, gear of looking, seeing, observing and fixing.

For more than four decades, von Poser has been constantly engaging with drawing, daily recording the infinite expressive possibilities of marking a given surface with strokes, in the guise of something else. In his obsession with fixing his visual observations, he managed to build a body of work that, due to its coherence, constancy, technical virtuosity and lyricism, proves the curious permanence of this more traditional, at the same time subversive of the works. The drawing of the human body, the greatest herald of this tradition, is, in turn, an ambiguous actor of this trajectory. Omnipresent, yet unexplored, simultaneously organizing and disaggregating, he conditions and comments on the entirety of his production, the image of their salsa bodies constituting the key to his work. In her drawings, the represented body speaks as loudly as her marker gesture, sketcher and drawn, coming together to give rise to something new. Dissolved artist and model, they both become drawing, a tactile and undying suggestion of a lived and past encounter. As the artist said: “If the drawing can be considered loving in its relationship with the gaze, this condition concerns the meeting of the charcoal trace with the paper, the meeting of the model with the other images projected from her body, the meeting of the artist with their desires and fears.” From these three encounters, von Poser’s drawing is engendered.

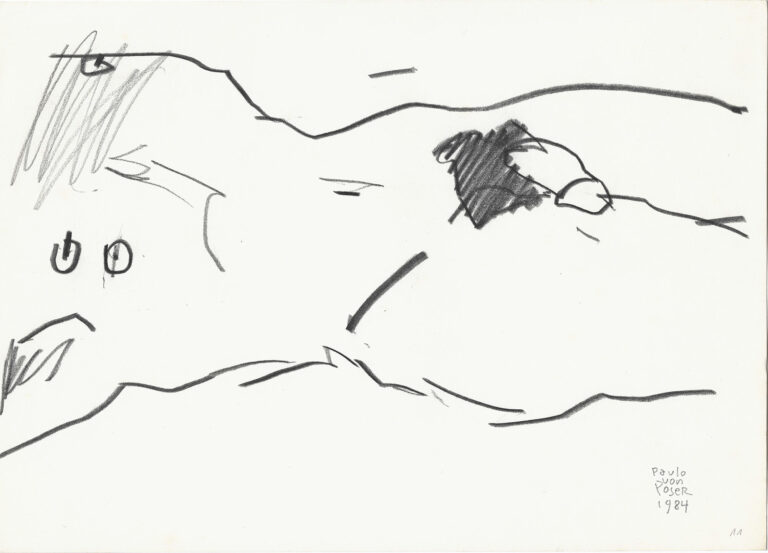

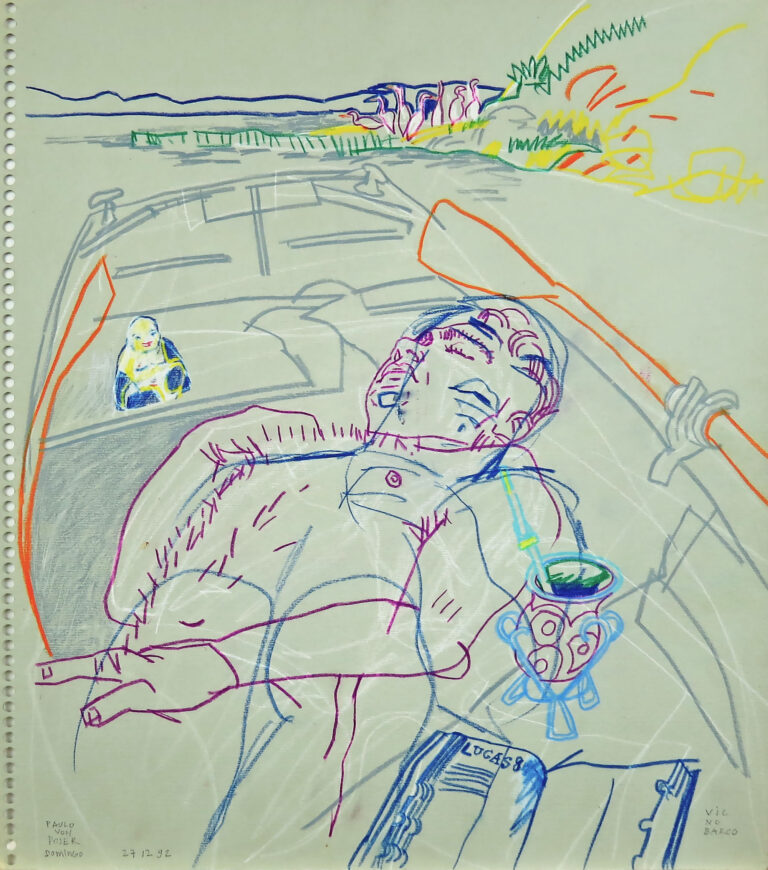

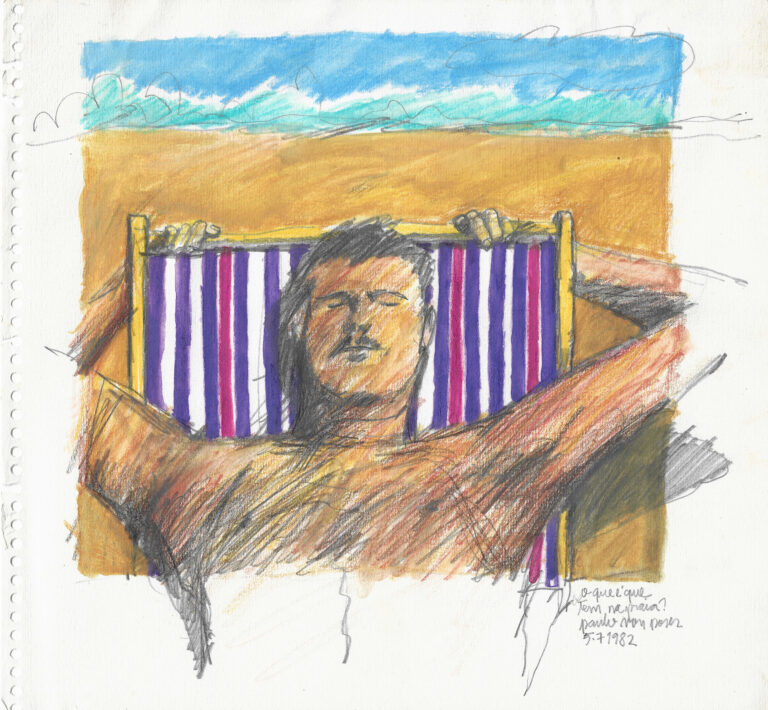

The present show seeks to give shape to this continuous production through just over twelve drawings, which in their entirety focus on the male body, and almost entirely on the undressed male body. The only two drawings that do not incorporate the male nude are Muso [Muse], from 1983, and Gustavo, from 1985. Dating from the early years of von Poser’s career, they present characters, known to the artist, sleeping, unprotected from the gaze that scrutinizes their relaxed bodies in full vulnerability, far from the artist’s desire while being preserved in their secrets and intimacies. The virtuosity of these drawings, as well as another from the beginning of his career, O que é que tem na praia? [What is there at the beach?], confronts us with an artist in full control of his technical powers, his coloristic knowledge and the precision of his lines being beautiful examples mastery, as well as master of his expressive possibilities, at that moment sprinkled with a sweet melancholy. The lack of protection of these models, objects and victims of the gaze, takes us away from them in a crooked question, amalgamating the hidden dream of these bodies to the personified desire of the artist.

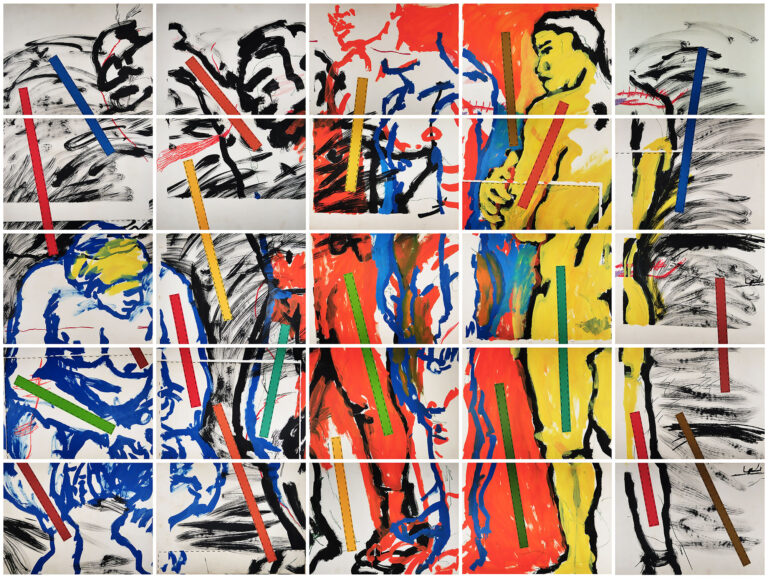

The set presented, with its cropped angles, their bodies limp from laziness or sleep, comfortable in their entirety and imperfections, anxieties and pleasures, is the testimony of an artist with a warm, attentive, close and careful look whose sensitive foundation is the act of looking at the world and return its beauty with shapes of rapturous precision. His curiosity for the things of the world, his fascinations and preferences, as well as his libido, exemplified in the Self-portrait with Overcoat diptych, are shown in this selection, as well as the choreography of his body in the act of making lines, traces and scribbles, and the many positions needed to execute them, overlapping each other to shape the mapping of your roving watch. By touching the contours of what he sees with the tip of his eye and pencil, his drawing is structured little by little, like an accumulative and non-linear cartography of his own body in the act of looking.

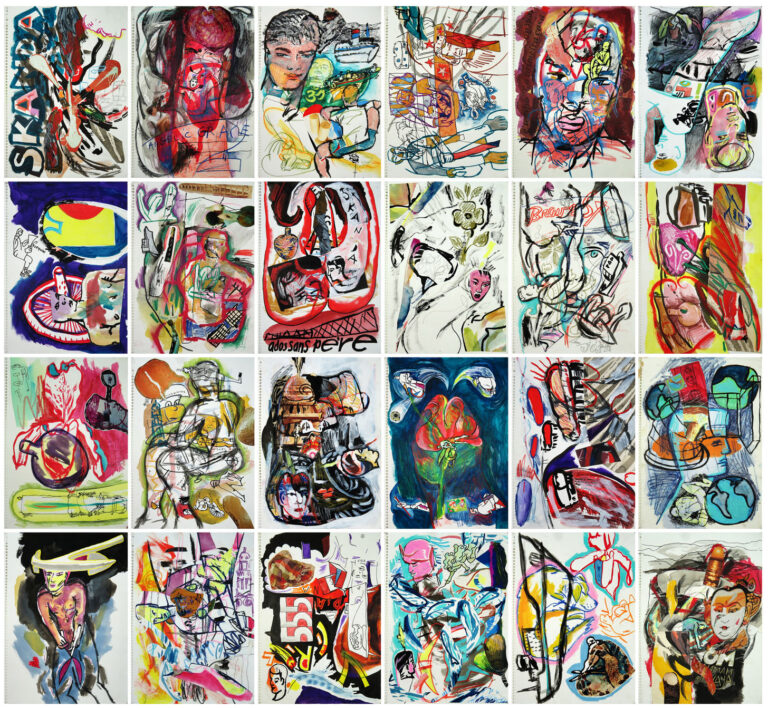

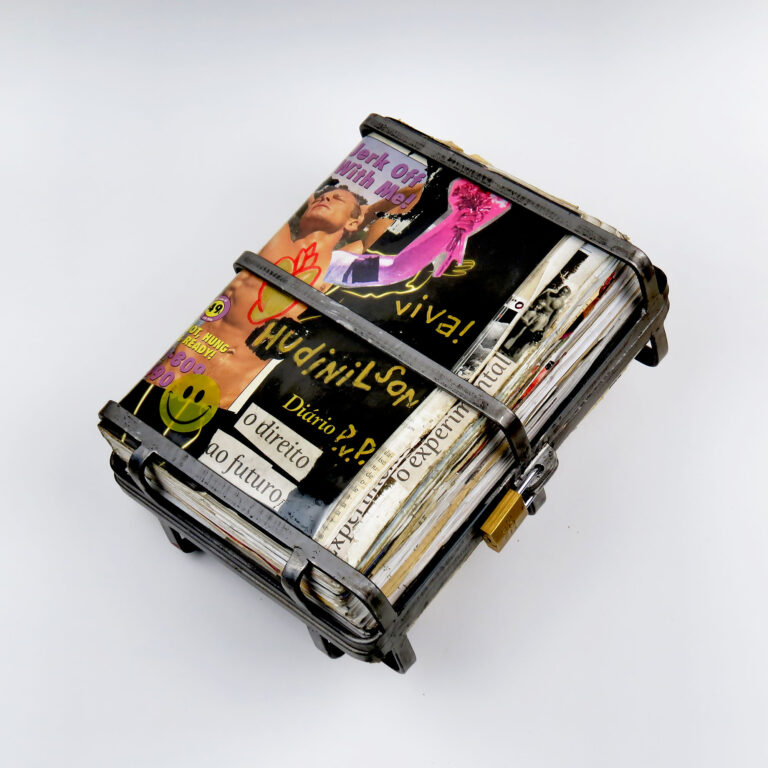

Let us not think, however, that this cartography, certainly the most lyrical, carries with it only the Apollonian purity of the beautiful forms. On the contrary, in the scribbles and scribbles, in the almost incisions made by the artist on the paper, in the blunt erased lines and scratched lines of his drawings, we are brought into contact with something rarely discussed in von Poser’s work: the restlessness and disquiet of the your look. In his drawings, this anguished restlessness is constantly present thanks to the restless marks of his hand. Outwardly placid, they are on the inside restless and boisterous, nervous as ants on an expedition, hence they are even more beautiful in their confabulations. The restless set of 24 Skanda collages is a great example of this characteristic. Its title, which alludes to the Hindu God, symbol of the balance between strength and goodness, power and beauty, and representation of the ability to perceive the difference between the true and the illusory, the real and the unreal, confronts us with the essential quality of that work. Fragmentary in their components and meandering in their compositions, they are structured from opposites, from contrasting elements such as the coincidence of sacred and profane, sexual and spiritual images, as well as opposing techniques, wet and dry, theoretically inimical, but here admirably agreed.

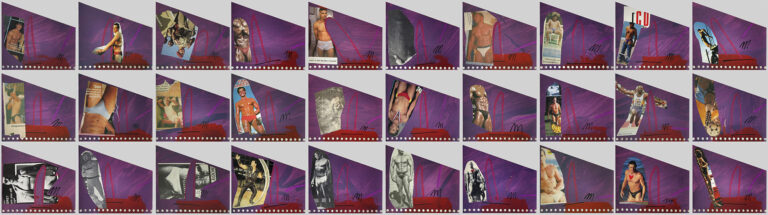

Another point that must be made here is the innocence and naivety of von Poser’s gaze. Not subjecting himself to the guilt of contemporary knowledge, he embarked along his trajectory along the path of candor and simplicity, of what, however uncomfortable it may sound to us today in the kaleidoscopic aesthetic universe in which we live, must be called beauty. As a result, his work carries the honesty of a subjective look, true to himself, lacking in its purity and colorful in its preferences. He is an artist who presents himself to us naked, uncovered and unprotected, revealing himself completely, without filters. The production of the harmony of its lines is possible thanks to these qualities. The Body Pleasure group of collages demonstrates this characteristic. In them, images of male bodies taken from pornographic and gossip magazines or art books are presented as objects of the artist’s fascination and desire, one of them having a small heart engraved on his chest. In these tiny collages, the artist not only represents the naked body, but also presents himself naked in his ambitions, undressed of insincerity or dissimulation. The simplicity of the gesture, combined with the absence of malice in such a construction, almost adolescent in its candor, confronts us with a Hellenistic search for the ideal forms of the male body, one in which desire is constantly present.

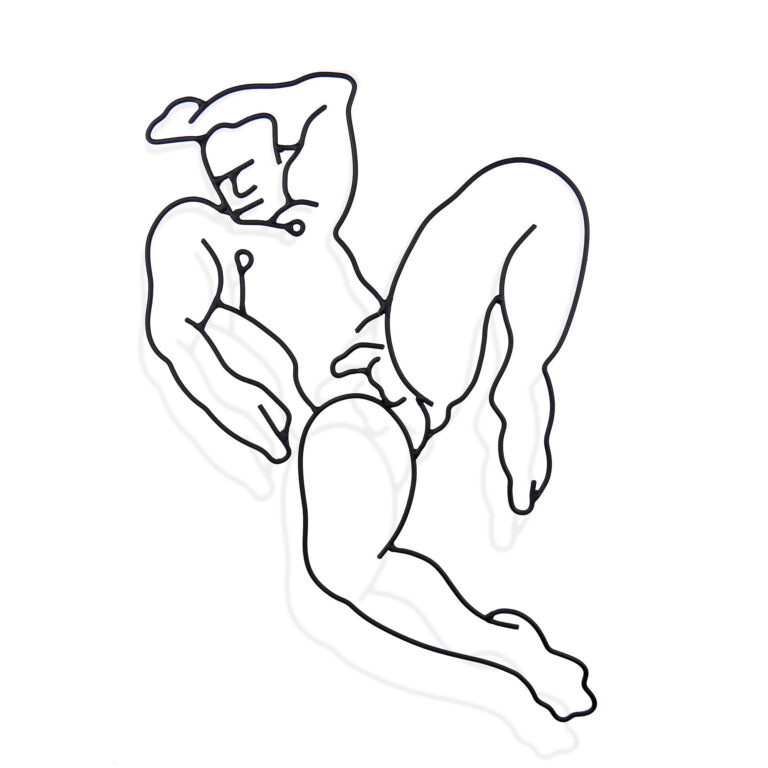

But it is in Autorretrato com lírio [Self-portrait with lily] that the purity of her naivete is most explicitly revealed. Sitting in the lotus position, the artist presents himself with a brush in one hand, a tool of his trade, and a lily in the other. Naked and with a watch on his left wrist, he faces us with his gaze, undressing the one who stares at him in the same way he presents himself naked. The lily, a symbol of purity and perfection in the Christian tradition, points to his aesthetic pursuit, while revealing his innocent intent. His position, of stability and perfection, indicates his intimate contact with his own body in the act of portraying the world around him. Finally, the clock makes us face time, its inexorable passage, its voracity to consume the beauty of bodies, as well as the end of all things.

Naked in their ambitions, the drawings presented here suggest the strength existing in the search for a certain beauty, despite the horrors of history, humans and times. Since it reminds the present author of a poem by W.H. Auden on the arrival of man on the moon, which in its grumpy wisdom serves as an apt defense of that same quest:

Our apparatniks will continue making

the usual squalid mess called History:

all we can pray for is that artists,

chefs and saints may still appear to blithe it.

![Autorretrato com lírio [Self-portrait with lily]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/PVP_Lirio-768x1030.jpg)