A map of moments – drawing and painting

What memories do we carry of moments that, we believe, are remarkable for us to be who we are?

– Surrounded by unfinished paintings in his apartment in Recife, Fefa Lins paints a still life. While most of the artist’s paintings involve a long process of work centered on portraits, this one was done in a few hours and does not directly depict a human body.

The stains that formed the painting make a cigarette box, a candle, an asthma bomb, a fruit recognizable: traces of the uses of some body. As has become common in his work, after all, Fefa starts from a composition that makes him rethink his own practices. Hours later, a video running through the parts of the painting would appear on his Instagram profile —

“balance and melting studies to the sound of Kamasi Washington; still life like me”.

– At some point in 2010, a professor of the architecture course at UFPE receives a work from which she would immediately discount two points. It was a drawing made with squares and a caliper on parchment paper. As a sauce, Van Goghian inclinations reconfigured it: orange sky, reddish grass and blue house, colored by colored pencils. Years later, the interest in composing through color would recur; the technical drawing, no. Architecture, Fefa tells me, is not necessarily a course for those who like to draw.

– Somewhere in Casa Forte, sacred paintings decorate a middle-class house: a holy supper in the living room, a white Jesus next to the parents’ bed. In her room, Fefa is a teenager drawing — between anime characters and an interest in painting — a portrait for her girlfriend.

– At the height of Facebook, portraits are exchanged in the group “Selfless portraits das Minas”, based on anonymous raffles that paired participants. Between drawings of himself and other people, Fefa starts to use watercolor paint and, while he fables curves and angles, he intersperses the graphite strokes with the ink stains. Painting and drawing, it seems, make bodies in different ways.

Painting-performance

Which poses from Fefa’s work are imitable? Which ones are familiar? Which not?

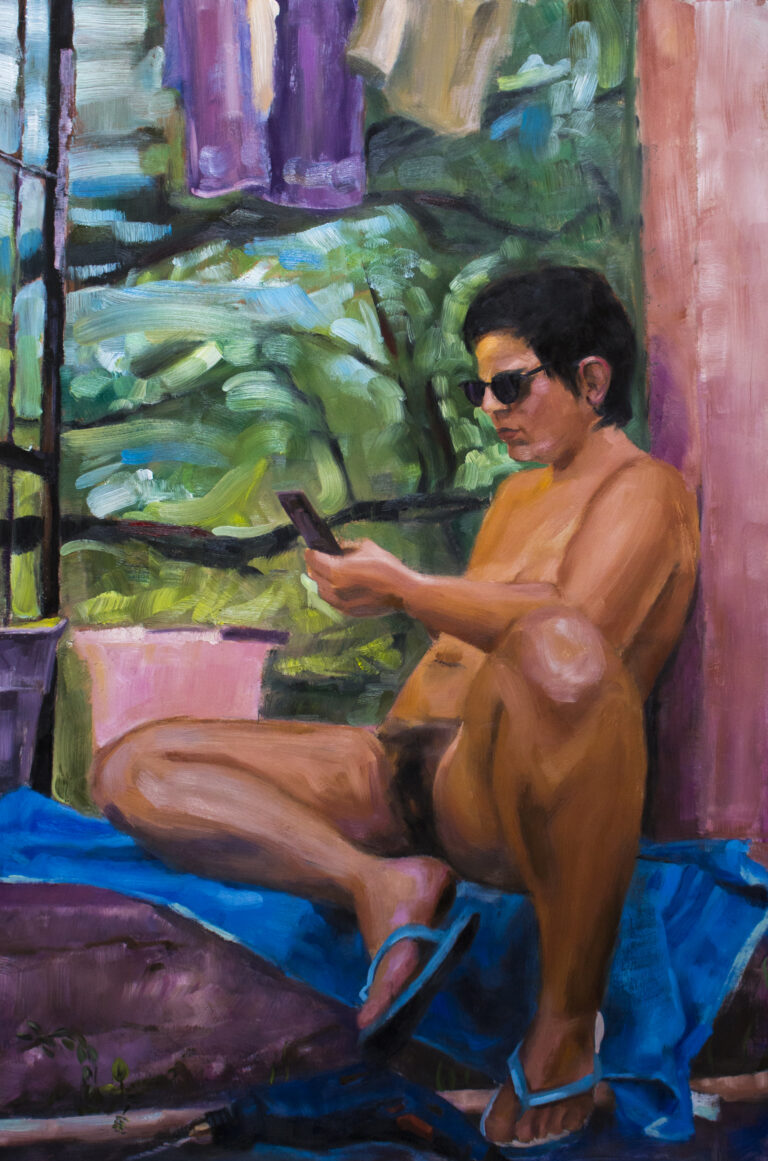

Sitting on his bed, Fefa Lins looks at his cell phone. The device is connected to your camera, placed on a tripod in front of you. Looking at the smartphone, Fefa sees what the camera sees. Naked, he spreads his legs and looks at his own pussy. It changes, perhaps, the position of the face, rearranges the limbs, organizes the torso, makes choices about how closed your face should be. Looking through his cell phone, which reflects the camera, which points at him, he takes the picture. Hours later, on the computer, he sees his own image: he changes lights and colors, paints and glues digitally. He transforms the background, appropriates materials from the internet, other paintings and his photos.

The photo of your body — which started with a composition between gestures staged and shaped by everyday life — is recomposed in digital. Later, the image would be projected onto a canvas on which Fefa would initiate a crisis-inducing process: painting and rethinking himself once more until the image he paints stops provoking him to paint more. Thus, Fefa’s body is shaped (in

everyday), rechoreographed (by himself), triple computed (on cell phone, camera and computer), reformulated (in Photoshop) and redone (in the prolonged act of painting). Each of these steps, he tells me, speaks to itself.

Investigating one’s own performance is an old habit for Fefa, who, from childhood, became proficient in reflecting on his behavior from how it was regulated in terms of gender. The poses, objects, fictions and their love relationships appear in the painting as they present and expand her body. Thus, as he points out, “the image is the very gesture that will set the tone of the painting”. His body exists before the image, but also during and after, and, he says, the thought of painting is always present in his process, but the work exceeds it.

When talking about his practice, it is not for nothing, then, that Fefa resorts to terms such as performance, editing and digital manipulation. His painting is multiply performative; not only because he stages his body, but because he emphasizes that painting is an act in which the performer is in the making of himself and the painting. He reminds me that being a painter was never “just painting”: it always involved certain techniques of seeing, both in the artistic use of the camera obscura and in the hegemonically trained gaze of many painters. Seeing and appearing are acts, and, certainly, doing oneself (in everyday life and in art) is a process that needs to articulate regulations and fabulations. Fefa’s painting, then, appears to be a performance painting, not only because it starts from the gesture and because he invites a succession of his actions, but because it is an apparition of himself that transforms who paints and, perhaps, who sees.

A desire to paint the desire

At what moments in our lives, desire and elaboration blur?

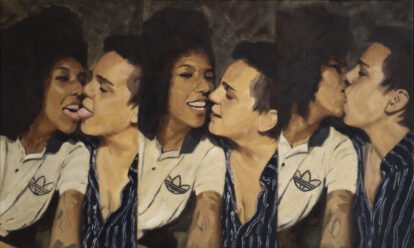

After more than an hour of interviewing, I ask Fefa Lins what is his interest in portraying other people, when most of his work is focused on self-narratives. Without thinking too much, he considers: “maybe to talk about who I am within a relationship, who I am within this collective”. With a little more hesitation, he adds that sometimes he just wants to paint “that pretty face”. Minutes earlier, Fefa was talking about how he discovered the pleasure of manipulating paint in the exploration of painting itself, especially after taking intensive courses in 2015. The techniques with which Fefa works in painting involve manufacturing

layers, filling the frame with different tones, mixing materials and constituting images by thick and thin spots, creating stretches and details, walking through the most figurable and the most abstract parts of each face, body and place. He takes pleasure in the work of painting, creating the image already materially, with size and weight, “as an object itself, something that exists”, as he says. They are images that are made with his gestures and are, for him, tactile. The artist tells me about an erotic pleasure that appears when he is working with paints and explains that the paintings often come back to him in sexual moments in his daily life. Aesthetic pleasure and sexual pleasure share a lot in common and the two mess up the desire to paint with the desire that emerges from the painting. Sometimes painting is also wishing for a pretty face.

Report dissent

What do we want to see when we seek to see others?

“Work is not my body, work is a reflection that I have about my body, it is a way of interpreting what could be about other bodies, but I feel comfortable with mine”, says Fefa Lins. In the previous sentences, he had stitched together the problems of paintings that look at women from patriarchal desires, the yearnings around ending up looking

very self-centered and the limits of wanting to account for how other bodies can appear. The reflection is consistent with a recurring concern: that his professionalization as an artist has to do with an understanding of his work as a form of communication, reflecting on paradigms of art. Thus, his investigation seems to act on how social and structural regulations are updated in his singular body.

More than linking himself to an idea of what representations of a non-binary transmale body would be, Fefa understands that turning to himself is part of his dissidence: “What we produce with this is something that is questioning for us also: you do the work and then he tells you a lot of things you didn’t know yet”. Because Fefa looks at her own body, she is able to properly communicate the links between gender expression, sexualities, desires, pleasures and sufferings, which resonate in other bodies. His work, then, more than just sticking to themes conceptually, seems to communicate — in the sense of projecting, making common — his affections and conflicts, which, then, are no longer his alone. This is what allows me, for example, as someone who deviates in such a different way from Fefa, to look at his paintings and, still, find in them some kind of reception for my own conflicts.

![Brotheragem [Brotherhood]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/broderagem-REP-768x729.jpg)

![Voyeuristas [Voyeuristic]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Fefa-Lins-Voyeuristas-768x457.jpg)

![Preparar o terreno [Prepare the ground]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/chama-barba-2-768x1646.jpg)

![Ostras à trois [Oysters à trois]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ostras-a-trois-768x602.jpg)

![Seios fartos [Big breasts]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/seios-fartos4-768x1097.jpg)

![Motoqueira [Biker]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/motoqueira2020-768x768.jpg)