ANA BEATRIZ ALMEIDA (1987, Niterói – RJ)

In her inseparable work of performance and research, Ana Beatriz Almeida takes up paths that were planned annihilated by the dynamics of western colonization. In recent years, the artist has dedicated herself to the investigation and practice of rites and dances of African origin that propose dialogues on divinization and the body, healing and death, sacrifice and passage, the vital force and the feminine, nature and black slavery in Brazil. In this broad field that lies between the poles and the epistemological limitations caused by the structure of Eurocentric thought, Almeida proposes bridges of continuity from the rescue and permanence of African narratives in Brazilian lands. These bridges – affective and ancestral –, drawn continuously in a series of performances by the artist over a decade, led her to meet her family in Benin.

The artist presents an intrinsic link between the material and spiritual planes in the thought structures of different cultures of African origin. This connection even attests to the shear imposed by the whitening political dynamics that separated even what was unthinkable to be dissociated: the body and the spirit. In processes in which the body and the names are together, Almeida reaffirms that these bodies, historically subjugated, bear royal, divine names. In their surrender rituals, they navigate nature through natural and supernatural flows, in a forward movement that is simultaneously a return movement. Then, the dignified, ritualized and ornamented body returns, restoring everything that was violently taken from it in the dynamics of oppression of African societies in colonial clashes, which are structurally perpetuated in contemporary times.

With a work that is poignant for its precision, Almeida operates at this point of weld between anthropology, ethnology and performance, rescuing forbidden narratives and images in the usual way of telling the history of the formation of Brazil, with a focus on the Bahia´s Recôncavo. It deterritorializes and decolonizes Brazilian forces in which the spiritual and the material are one. She calls her ancestors by name, writing on her body an extremely dense and complex history, consolidated over millennia. It reiterates an existing reign, as if clearing the ground over the age-old roots of a long-cut tree, which is blossoming again.

DANIEL ACOSTA (1965, Rio Grande – RS)

Daniel Acosta explores spatiality on an expanded scale, from the purposeful increase of usually ornamental and small-scale motifs, to the very human relationship with public space, with the city and with the environment. The artist proposes to think about space through the sculpture platform, but beyond the usual smaller scales. In doing so, it proposes a questioning of the tenuity that separates contemporary classifications between sculpture and installation, with a transdisciplinary artistic approach with architecture, design, geography and the phenomenology of space.

One of the artist’s central concerns is the relationship of spectators with his works in space, making them, in a way, users. Acosta thinks about space by portraying its forests and natural landscapes in synthetic materials, allowing the questioning of human interference in the natural environment, reiterating that the very notion of naturalness is artificial.

After all, should human interventions in the environment be considered natural, insofar as human beings shape space to their needs, as a member of an ecosystem? Would artificiality be inherent to human production and its vision of nature? Acosta’s work enables a critical reading of the unsustainability of human dealings with the environment, as well as an incentive to rethink fair ways in which citizens relate to the space of the effervescent cities in which they live.

With an ironic tone, Acosta sometimes uses extremely standardized materials, such as Formicas that imitate wood cut with laser machines, to represent a wild natural landscape. Hostility is not found in the savagery of the forest, but in the aggressive thinking of contemporary man and in his dynamics of production and occupation of space. Green masses of leaves that crown treetops become colored vector planes, converted to a technological language so that machines could replicate them unrestrictedly and unsustainably.

The artist proposes these natural cutouts that can be transported, as well as in Islamic traditions, where the rugs worked as portable gardens that could be taken anywhere, in order to maintain a veneration relationship to the care of nature through gardening. It revisits, in the history of art, the theme of the representation of landscapes in painting, engraving and photography, usually melancholic. When looking at these portable landscapes, instead of escaping the urban world – in the Latin sense of fugere urbem – we are reinserted in the artificiality imprinted by human beings on the landscape.

Acosta’s work alerts us that we are increasingly moving away from realizing that the communicative, linguistic and representational devices used by man are technologies of very high sophistication. Thinking about these hyperflows in contemporary art allows the deceleration of these dynamics and the attentive observation of their functioning, with critical points that jump to the eye and that aim to be debated by the artist. The representation of nature by man is, therefore, a meta-illusion.

FEFA LINS (1991, Recife – PE)

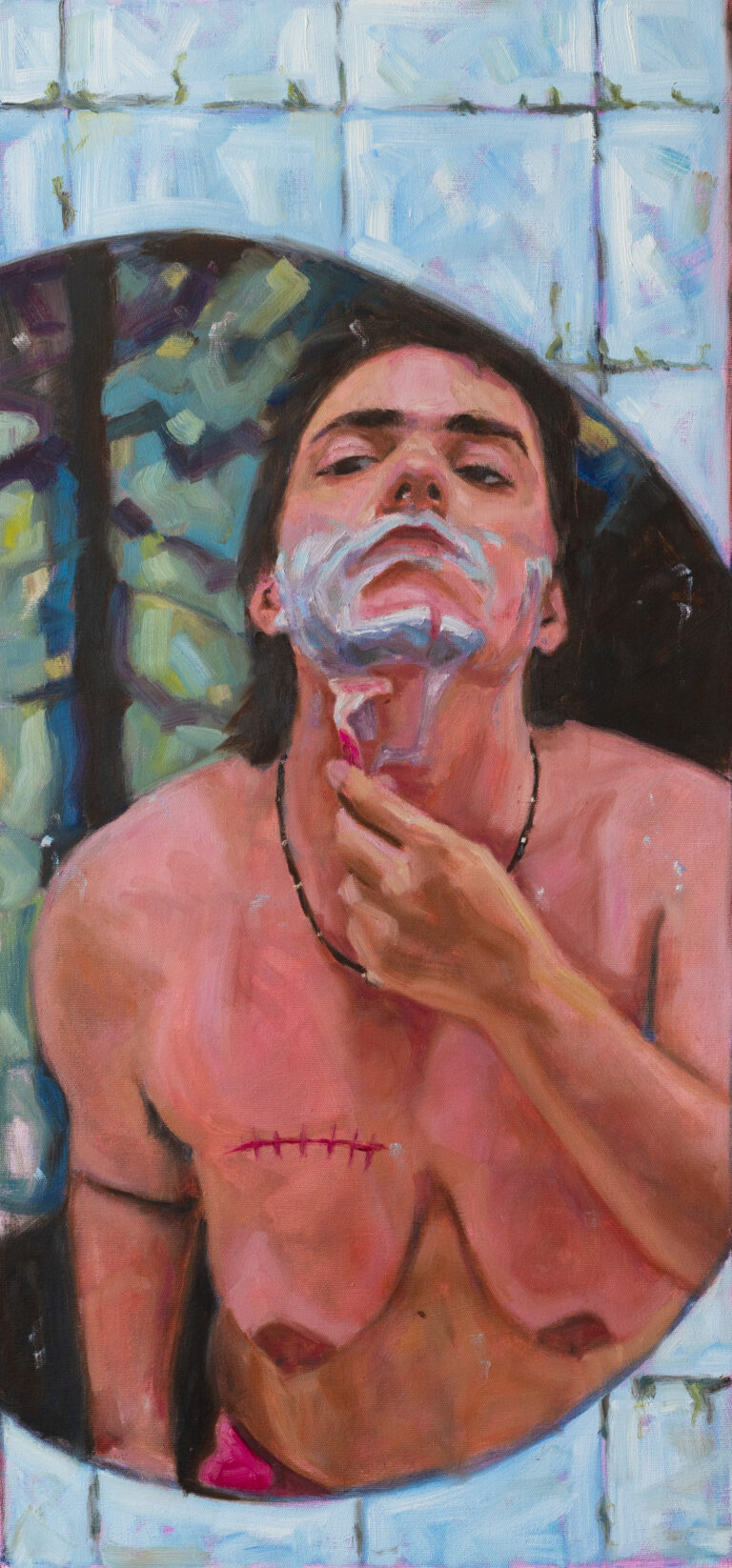

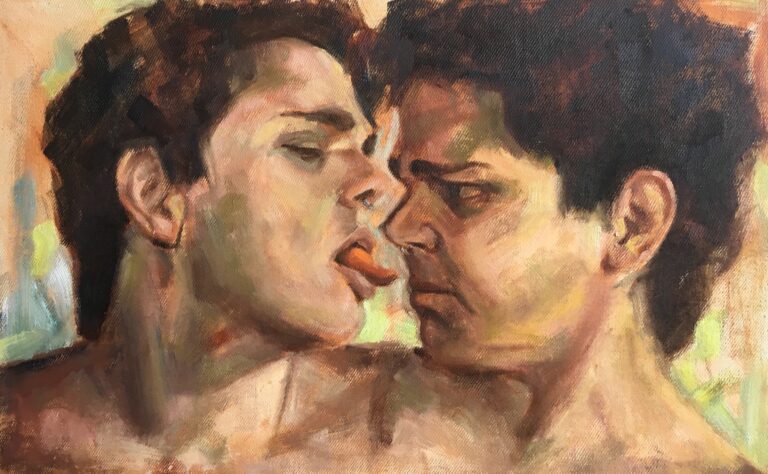

Fefa Lins proposes new ways of dealing with contemporary complexities, questioning and operating stigmatized classifications about the history of painting, discussions of gender and sexuality and the impacts of technology in the present day. The painter’s individuality is reiterated by presenting us with multiple and hybrid ways of observing the phenomena of current images through a canonical platform: oil painting on canvas. The choice of this platform can be read as a criticism of the limitations that certain artistic tools are restricted by historical and social ties.

The technological discussions engendered by Lins go beyond discussions about the body and also extend to the scope of digital communication and social networks. One of the most intelligent strategies of ideological contestation is to improve the technology imposed by the oppressor and to revert it, grudgingly, to its origin. The meta-revision of human technologies such as psychoanalysis, phallocentric symbolic systems and patriarchal social structures assertively criticize the neuralgic points of these constructions. In Lins’ work, rethinking the ever-changing society is also representing oneself in full transition. Like a mirror, Lins not only expresses a reflected image of the present social structure, making it examine its own dynamics of surveillance and violence, but also activates her body as a political image, when confronting reductionist and prohibitive transitions and flows.

In the painter’s works, the freshness and vivacity of colors bring an accentuated intensity to scenes and bodies neglected by history. The strength and importance of individual events, seen as commonplace or banal, are accentuated by the intense chromaticism of his paintings, with dreamlike atmospheres that transit between cotton candy clouds and fiery Dantesque landscapes. Scenes, usually private, in intimate places such as the bedroom, bathroom or bed, are wide open and shared with everyone.

With a full technical mastery of painting, the intimate relationship of light with bodies and the use of current devices – such as digital photography – in the composition of his works, the painter reaffirms the obsolescence of technologies that still try to perpetuate outdated classifications, such as gender binary. Gender and sexuality technologies are always vigilant technologies, accentuated by the hyperconnection of information in the dataosphere. Lins’ work encourages the centrality of the peripheral body: not as a target of patrolling, but as protagonists of hitherto veiled narratives. In a quantum world, Lins’ work presents us with a plural, hopeful and combative horizon that welcomes the multiplicity of the self, both in the body and in time.

SHAI ANDRADE (1992, Salvador – BA)

Through a reflective and mirrored apparatus, such as the photographic camera, Shai Andrade proposes a critical reflection on the past, writing a visual narrative for the future. This epistemological duality is a critical analysis of the erasure of black histories, added to the attempt to whiten the fruits of miscegenation and cultural hybridisms that take place in Brazil. The meticulously listed genealogies of the white families demonstrate an artificiality plastered, contrasted and opposed by the broad movement of forces photographed by Andrade.

Like a palimpsest, parchment that is periodically scraped to make way for a new space for writing, black stories are continually victims of an ephemerality of the oral narratives that structure them, lost in a system where only the documentary record is considered valid and manages to be perennial (whitened, scraped paper, wouldn’t it be paper without history?). Make no mistake: the iconoclasm of black culture is historically planned.

For years, Andrade has recorded, through photography and video, performances and expressions by black artists who share her same narrative values. Recently, Andrade has set herself up as an artist, writing her own narrative by investigating her family, cultural and spiritual genealogy, portraying everyday scenes that combat the stereotyped exoticism that parasitizes these images. The artist does not only propose an isolated individual investigation, but inserted in an articulated structure that involves several voices, discourses and realities. As in a healing ritual, Andrade moves and glorifies these images, which dance and drag the light in her photographs, behaving like ever-present entities that inhabit the world of matter and idea, claiming the divinity of the human and the humanity of the divine.

In Andrade’s photographs, the movements of affirmation and denial referring to historical identification assert themselves with protagonism. The artist gives back to her subjects the look that has always been neglected, usurped by force by the dynamics that revolve around the white man. In Andrade’s photograph, there is no “pretending not to be seen”. In addition, the artist questions the patriarchal paradigms that direct social dynamics and proposes a matrofilial structure, centered on the female figure as the root of collective memories. The dynamic between master and apprentice, therefore, becomes a respectful hierarchy of female priesthood.

Andrade constitutes, from these dynamics of intergenerational narratives, a heritage to be inherited and rescued. In a reality in which almost everything was taken from her, the artist resumes the construction of this cultural heritage of the black people, rebuilding the house, the temple, the structures, the lights, the colors and the history.