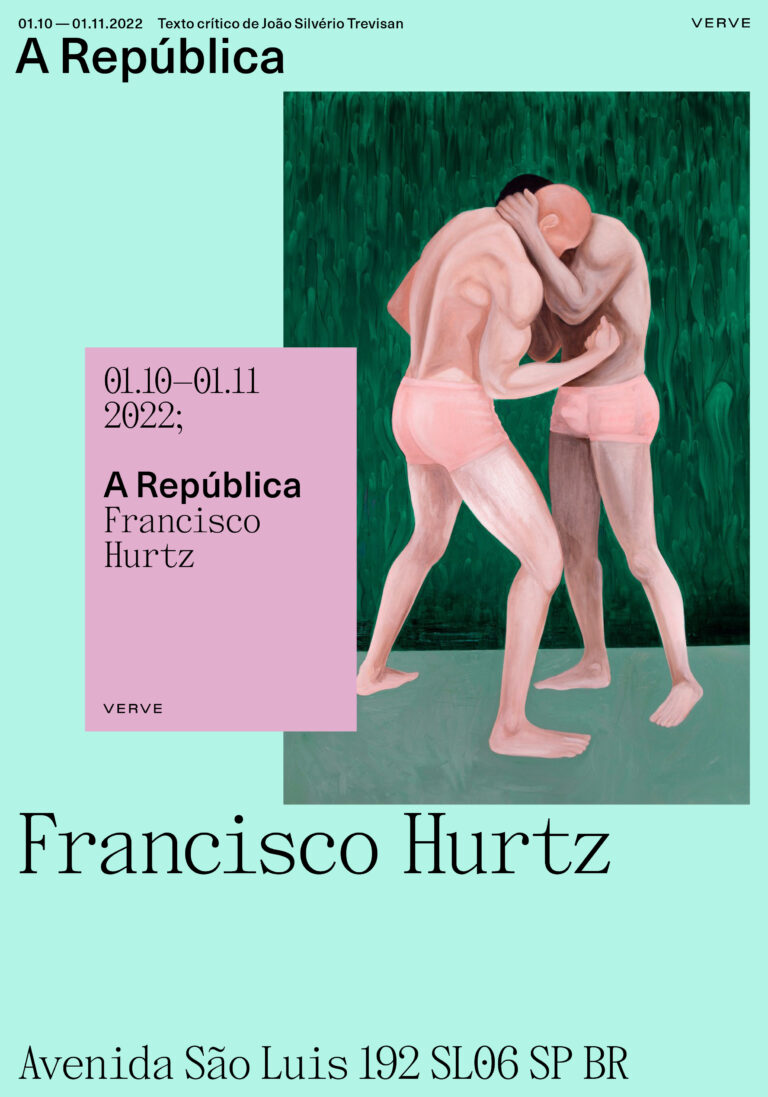

What enchanted me right away, when I got to know the work of Francisco Hurtz, was the savagery contained in its simple, essential lines. And I thought that feeling was familiar to me. Gauguin had something like that, mutatis mutandis. But there is in Hurtz’s clean lines a connotation that distances him from the supposed innocence of the French’s post-impressionist traits: explosive sexuality. Not that it is explosive outside the parameters of the work, but implosively, I think. Hurtz’s work implodes like a grenade thrown into the sea from the interior nothingness, where it causes almost unspeakable shocks. We know where the blow comes from, but we cannot describe it. Could this be a death drive? Absolutely not. It is a sexual drive, the result of pure reality. Then comes the revelation: there is indeed an innocence in Francisco Hurtz’s work, but the opposite. In Gauguin, innocence is forged, in bodies colonized by the French artist’s gaze. Here, there is Brazilian innocence in its raw state. It is, in my view, the innocence that knows how all radicality is deadly. Death presents itself in his work with an affirmation of innocence, the complete opposite of thanactic morbidity. We are far from the little gun, that is, the little game of bandit and good guy in the hollow head of someone who wallows in political infantilism – and believes himself to be unbeatable. In these works by Hurtz, weapons are weapons. Not to scare, not to pose. They are clear objects with nostalgia for sex.

Here, naked male bodies cross gestures with guns that spit bullets but could spit shit. There is a strong sexual tension, close to David Cronenberg’s cinema, especially when it meets J.G. Ballard’s novel Crash. There, orgasm occurred only possible in mutilation, in which pieces of steel from cars were mixed with the bodies in pieces glued together. Here in Francisco Hurz, what can be seen is the critical and biting pleasure of metallic legs as an extension of weapons. The strength of weapons is multiplied by the mechanical limbs of men. The phallic force of the killing apparatus is transferred to the sexually tensioned prostheses. But still, there is no morbidity, even when libido-boosting, as in Cronenberg/Ballard. Far from the stupid joke guns, for being idiotically phallic, here the guns take their place in the bodies and interchange, symbolically, like new phalluses. Naked men look at each other or show each other. They are entirely there, still, in their persistent muteness. Both self-contemplation and exhibitionism are not erotically posed: they are gestures and looks charged with libido for their innocence. But there are also crime scenes. Armed men, sometimes with their prostheses, sometimes without, are nothing like models of beauty. They are common from the periphery, wearing Hawaiian sandals and loose shorts, or uniformed soldiers revealing themselves with their pants down. If they’re naked, they don’t seem worried about looking what they’re not. Even when erect, their phalluses exude innocence, as if confirming: “Look at me and my dick”. The critical force of the works in this exhibition speaks of bodies that ARE. These bodies live in a state of exile, often haunted by crime scenes that pervade the imagination of those who go against the grain of heteronormativity and know the underlying violence in a time of resentment that took hold in power – to promote hatred. Despite this, these bodies ARE.

In short, therein lies the contemporary element of resistance: in queer ARTivism. Francisco Hurtz does not hide that he is active, and his activism unfolds, beyond the denunciation, in the art and celebration that they affirm. So we come to the heart of the matter: Resistance is poetic. And Poetry, in turn, has a brutal Resistance component. These are familiar feelings for me. There are no boundaries for poetic expression. If the Poetry in these works is wild, it is in no way different from the violence that is intrinsic to Poetry. Because all Poetry frightens us and mobilizes us, due to its capacity for revelation. Poetry is Epiphany in its purest form, like a grenade thrown into the sea from inland nothingness. It is contained in the primal cry of the poet Roberto Piva: “I am a machine gun in a state of grace.” In Francisco Hurtz, our bodies are ours, with everything they have a right to over us and we over them. For his innocence, for his pulse of life, what his work tells us, with absolute conviction, is that the sky is also Poetry.

Make way for the bodies and their asses. And long live Roberto Piva!

![Assombração [Haunt]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/siteassombracao_a_republica_2022-768x896.jpg)

![Coração Vermelho [Red Heart]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/sitecoracao_vermelho_2022-768x960.jpg)

![Homem Partido [Broken Man]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/homem-partido-o–capital_2022-768x959.jpg)