Paris, 1889. The Eiffel Tower had just been inaugurated. The construction divided opinions: some admired it as a symbol of French progress, while others were reluctant to have the gigantic tower erected in a burst in the landscape of the city. The French poet Guy de Maupassant was one of the opponents of the project: however, for a long time, he had lunch every day in one of the restaurants on the first floor of the iron tower. When asked about this apparent contradiction, he replied that this was the only place in Paris where he could be and not see the tower.

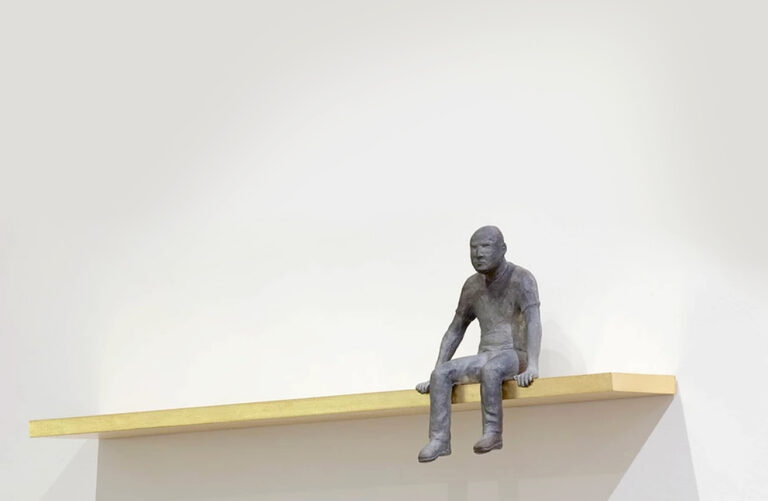

The recent production of the artist Gustavo Rezende seems to come close, in many points, to this story. The repeated production of sculptures depicting Maxwell, a character who presents himself as a kind of alter ego of the artist, does not fall into a self-absorbed act or a narcissistic repetition. It constitutes, however, a solid body of work that aims to tackle questions specific to the field of history and theory of contemporary art, without neglecting the contributions of modernity to the sphere of sculpture. In this way, within himself it is the only place from which he cannot be seen: by adopting his individual physiognomy as the main illustrative tool of the narrative, the artist can, finally, abandon this theme and stop at essentially intellectual, artistic and sculptural questions.

Rezende’s inquiries about the artist’s positioning in contemporary times deal – among many other subjects – with the duality of the internal and the external, the individual and the collective, the vision of himself and others. Just by looking at the angle at which they are displayed, it is not possible to distinguish whether the artist’s sculptures are hollow or massive, rather what the spectator believes them to be. In an air close to philosophical skepticism, incisively discussed in his works, especially in the late 1990s, the artist raises strong questions about appearance and essence – or the shell and the core –, principles dear to the technique of sculpture, especially about from yourself. These crucial points are directed by Rezende to a meta-artistic discussion, which concerns much more theoretical questions about art than individual existential questions.

Rezende’s investigations provided him with a broadening of the imagery repertoire and a deepening of the theoretical framework, causing the artist to confront the artist with already apparently well-resolved answers to central questions of sculptural practice. The dialogues that the artist traces with modern principles – such as solid color, reproducibility and the monolith as a proposal for something pure – and contemporary ones – such as the geographical possibilities of sculpture, the impression of movement and the possible relationships of the sculpture with a base – appear a questioning restlessness in a panorama in which much has already been said, but not enough. The inexhaustibility of the subject, while comforting him, ravages him; but in the end, dissatisfaction is enough.

In the selection of works exhibited on this occasion, there is a latency dichotomous that Rezende has been exploring for decades. First, a poetic potentiality – traditionally fabled by the artist when defining his enigmatic titles, especially in his older works –, accentuated by a fictional narrative linked to figuration, provoking the need for the spectator to elaborate a sketch that is not officialized by the artist – sometimes even because it doesn’t exist. In a second moment, there is a contingency of movement characteristic in his sculptures, in an oscillation between the two-dimensional – especially in the reliefs – and the three-dimensional – in the works of greater depth. Rezende’s poetic and plastic development is robust at the same time as it becomes paradoxical, with assertive enigmas: a supposed “ease of understanding” of his work due to the family connection that one has with the human figurative aspect disappears the second he enters, even if superficially, in the artist’s intellectual universe.

The physiognomy of the sculptures took on their own by coincidence of fate. The Eiffel Tower was also not intentionally named: it stole the name of its creator, Gustave Eiffel, for convenience. Frankenstein is also not the name of the creature, as is automatic for us, but of the doctor who created him. This phenomenon usually happens when the work becomes bigger than its creator, extrapolating individual limits and analyzing ideological contributions to a broader context. This is one of the ways in which we can read the mirrored work of Gustavo Rezende.

![Maxwell Sentado [Maxwell Sitting]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/maxwell-sentado-perna-dobrada-1-768x535.jpg)

![Maxwell deitado [Maxwell lying]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/220527_verve_065-768x512.jpg)