“The more telescopes are perfected, the more stars will appear” — Gustave Flaubert

In recent years, the questioning of the three-dimensional field of Brazilian art has become the privileged territory for the emergence of new and good artists. And not only within the São Paulo – Rio-Belo Horizonte axis, but also in several other centers, these artists spread across Brazil have been resizing the canonical notions of sculpture, object, installation, expanding the limits between these modalities and the borders between them and the painting, design, engraving and drawing.

Within this expanded situation of current Brazilian art comes the production of Daniel Albernaz Acosta. Any reflection on this new situation of Brazilian art that operates within – and at the limit of – the three-dimensional, goes through its trajectory and expands with it.

To think about Acosta in relation to the production of other artists spread across the Brazilian territory is to reflect on the natural and cultural circumstances that their environments of origin exert in their productions. Although fully connected with the contemporary artistic debate, these artists did not extract formal solutions from the places where their pieces originated from their work.

On the contrary: in many cases, the basis of his works is precisely the attempt to debug visual stimuli originating from a native environment, through procedures and/or adhesions captured in the context of contemporary art… Daniel’s first phase works Acosta would undoubtedly be others, if it were not impregnated by the architectural/urban situation of Pelotas, in the interior of Rio Grande do Sul.

Born in Rio Grande (RS), Acosta emerged in 1989 from Pelotas, the city where he began his professional career as an artist and university professor. In a state without a sculptural heritage worthy of its interest, his production had as its primary ambience the Pelotas surroundings, full of architectural references built between the end of the last century and the beginning of this one. What captivated him was not exactly the eclectic and/or art-deco buildings that try to resist the criminal dismantling of real estate speculation, but the ornamental elements that adorn those buildings, and the fences that protect from the sight of passersby, the destruction of those icons of a past wealth.

Acosta’s works until 1992, 1993 – preferably made in purple plywood – were the poetic intersection between siding and architectural ornament, between the visible and the hidden. They filled the pain of the emptiness of a destruction in continuous becoming.

Ingrained in their original environment, incarnated in the reality of Pelotas, which housed them, those pieces seemed to discipline the ornamental excesses of Pelotas buildings, while transforming the material and color of the sidings that covered them into precious elements.

However, the significance of these pieces was never restricted to the fact that they were born as recreations of Pelotas’ architectural/urban elements. No. What is interesting is how Acosta, based on this, shall we say, affective base, managed to expand the very definition of sculpture, linking his work to one of the various currents of current Brazilian art, precisely the one that is formulated on the limits between painting, relief , sculpture and design.

The production of this period travels alongside – without ever getting mixed up, however –, and on the same path along which the works of artists who have been present in the Brazilian circuit for a long time walk. Like the production of Amílcar de Castro and Carmela Gross, those pieces touched the limits between painting and sculpture, projecting themselves into the three-dimensional, preserving the wall plane, literally or metaphorically.

In São Paulo from 1994 onwards, Acosta’s work underwent a substantial transformation. The impact of the chaotic metropolis within the artist’s poetics helped to deepen it, making it even more mature.

Among the various transformations, the change in materials stands out in the first place: whereas before Acosta worked preferentially with laminated purple plywood, in the new works plaster and formica prevail. From the warm character of the purple wood, the artist is then faced with the impersonality of Formica (metaphor of his feelings in relation to the new urban space that we are trying to encompass?).

Another visible transformation: if before the design universe was already manifested in the artist’s production, with his arrival in São Paulo this characteristic is amplified. Current works no longer inspire tenuous associations with industrialized objects from the 30s and 40s. Today they are explicit references to pedestrian safety platforms, floors, bathrooms, urinals… “indifferent objects” for public and/or private use, restructured by the sensitivity of someone who finds the new environment strange, because undoubtedly Narciso finds what is not a mirror ugly.

In a city that every day replaces the indexes of its identification, whose best synthesis is an avenue -, here nothing reflects us, except the windows of buildings, cars, and electronic security equipment.

As nothing represents us, and everything tends to present itself as a simulacrum, the human body – before the main territory of sculptural representation -, the body appears in Acosta’s works as absence (in the “urinary”, in the “bath”, in the “tiles”). Or as pure immanence, on the television screen. If in Rodin the body is matter, texture, volume and mass, in Acosta the body is its lack or pure surface without thickness (the television, the skin that is Formica).

Coupled with this total estrangement, the desire to build a panicked realism in the face of the non-reality of São Paulo, Daniel Acosta rescues for his production, which was previously totally attuned to the vernacular, undeniable erudite references: “Marat” refers to David; “Observatory” to Duchamp; “Basic Sculpture” by Carl Andre…

It is as if, faced with the rarefied reality of São Paulo – where everything is a façade or access route – the artist had the need to anchor his sensibility in some identifiable port. In this case, the history of modern-contemporary art, the only place where today Acosta and other artists seem to recognize themselves.

Having characterized the changes, it remains to draw attention to what remained constant in the artist’s work.

His current pieces, like his previous ones, continue to travel between the conventional definitions of painting and sculpture, with relief as their point of intersection. Acosta, despite the icy character of the plaster and the total impersonality of the Formica, continues to simultaneously discuss issues related to the traditions of painting and sculpture, maintaining his production in the fertile non-place of relief – a rich space of Brazilian art in the last thirty years. years old.

The move to São Paulo, the contact with the metropolis whose identity is not the old buildings, nor the nature, nor the local color but, precisely, the denial of any possibility of identity, did not make Acosta’s works change in this his basic feature: they remain dependent on the plane, discussing problems of painting and sculpture. At the same time, in a continuity that only enriches it.

To think about the production of an artist taking into account his relationships with the environment in which he works, it only seems possible at the end of this century, after the collapse of the values of the European and North American avant-gardes, which have become international. In the specific case of current Brazilian art, more and more artists, still young, put aside the excessive rigors of formalism, several of those trends, directing their artistic and aesthetic interests in the search for a deep synthesis between art and life, in its most wide.

The case of Daniel Acosta seems exemplary. The recent works that he now presents in São Paulo demonstrate how fruitful the artist’s exercise can be to let himself be penetrated by the stimuli of the environment where he lives, however hostile it may be. His works exude the environment where they were conceived and executed. If today the panic realism of his works overflows with a frequency similar to the works of Ana Maria Tavares and Iran do Espírito Santo (the most instigating translators in São Paulo today), it is because, without a doubt, they are the synthesis of a sensibility built elsewhere, not intimidated by the constant massacre of the self in a city like this megalopolis… and reacts.

![Rotorama - Sistema de giroreciprocidade [Rotorama - Gyro-reciprocity system]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DA-Daniel_Acosta-2@EdouardFraipont_18cm-768x513.jpg)

![Rotorama - Sistema de giroreciprocidade [Rotorama - Gyro-reciprocity system]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DA-Daniel_Acosta-11@EdouardFraipont-768x513.jpg)

![Paisagem Portátil 4 [Portable Landscape 4]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/paisagem-portatil-4-768x503.jpg)

![Laguinho [Pond]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/laguinho-768x527.jpg)

![Topocampo (quadrado) [Topocampo (square)]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/220404_verve_018-768x512.jpg)

![Estação avançada com paisagem portátil [Advanced station with portable landscape]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/estacao-avancada-com-paisagem-portatil1-768x611.jpg)

![Estação avançada com paisagem portátil [Advanced station with portable landscape]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/estacao-avancada-com-paisagem-portatil-768x617.jpg)

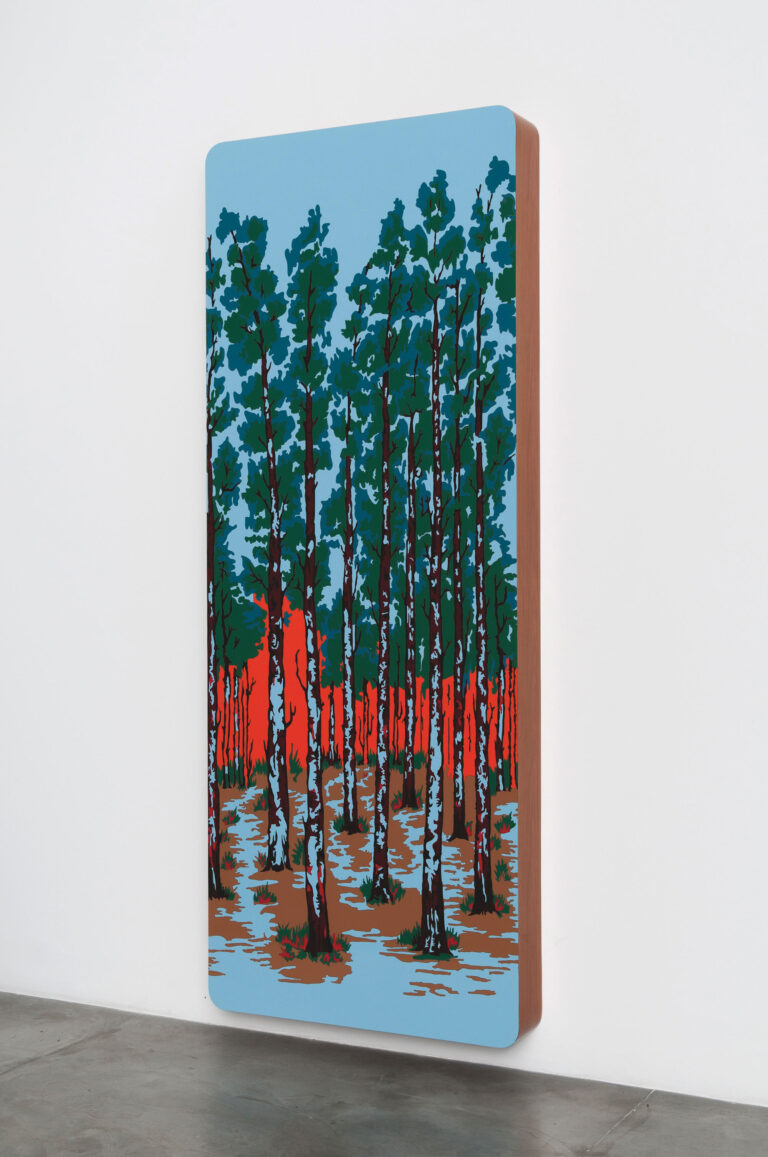

![Paisagem Combinatória Vertical M1 [Vertical Combinatorial Landscape M1]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/220330_verve_020-2.jpg)

![Paisagem Portátil (Unidade Compacta) [Portable Landscape (Compact Unit)]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/paisagem-portatil-2-768x633.jpg)

![Paisagem Portátil (Unidade Compacta) [Portable Landscape (Compact Unit)]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/paisagem-portatil-768x517.jpg)

![Constelação Laser 5 [Constellation Laser 5]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/constelacao5-768x1004.jpg)

![Constelação Laser 6 [Constellation Laser 6]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/constelacao6-768x1081.jpg)

![Tektoniks (Relevo Horizontal) [Tektoniks (Horizontal Relief)]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/tektoniks-relevo-horizontal-768x513.jpg)

![Animais lentos [Slow animals] (series)](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/animais-lentos-768x512.png)

![Estimado Selvagem (Leopardo) [Dear Savage (Leopard)]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/estimado-selvagem-leopardo-768x512.jpg)

![Estimado Selvagem [Dear Savage (Lion)]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/estimado-selvagem-leao-768x512.jpg)

![Conversa na piscina [Chat at the pool]](https://www.vervegaleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/DA-CP_OK_sem-fundo-768x318.jpg)